Call for ‘great observatory’ to succeed Hubble

Michael Banks reveals the highlights of the long-awaited Astro2020 Decadal Survey, which will define the course of astronomy and astrophysics in the US and beyond over the next 10 years

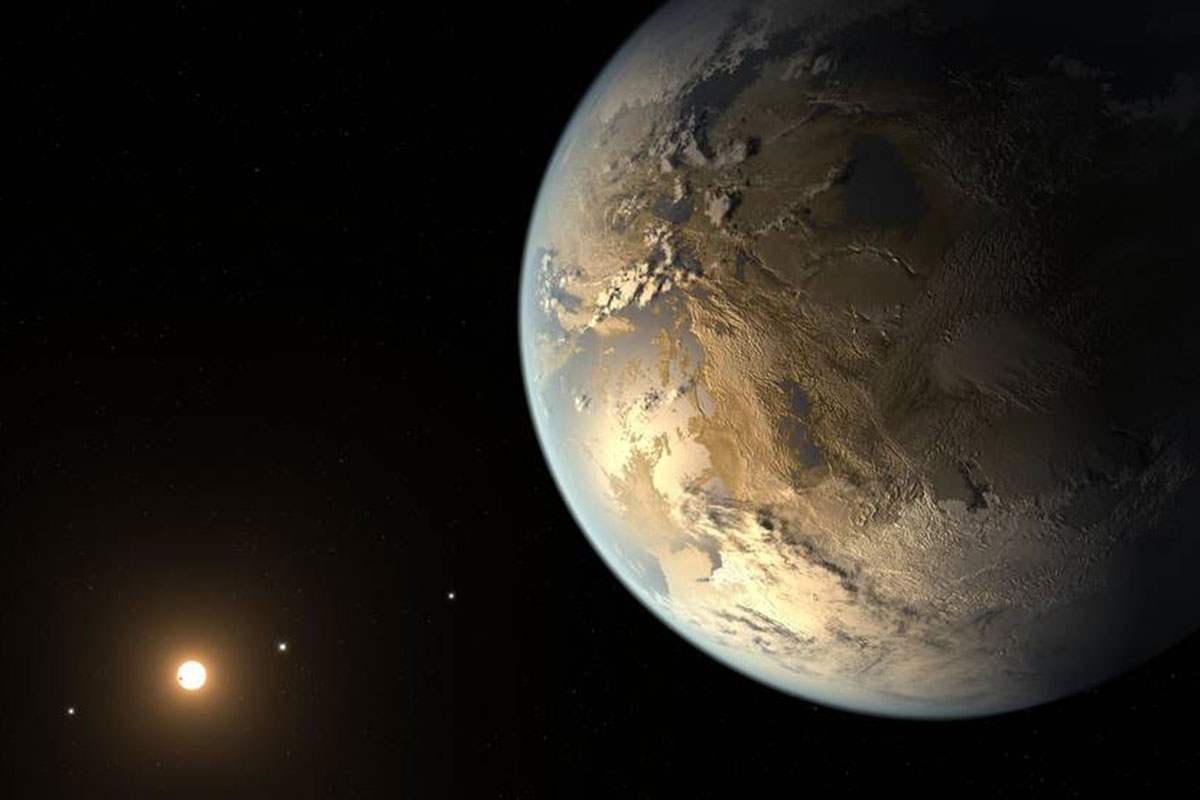

An influential panel of astrophysicists and astronomers has called for a major space-based observatory to be launched in the mid-2040s. This significant new mission would observe extrasolar planets that are 10 billion times fainter than the stars they orbit and provide spectroscopic data about the planets. The recommendation is made in a major, 614-page report released last month by the Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics 2020, known as Astro2020.

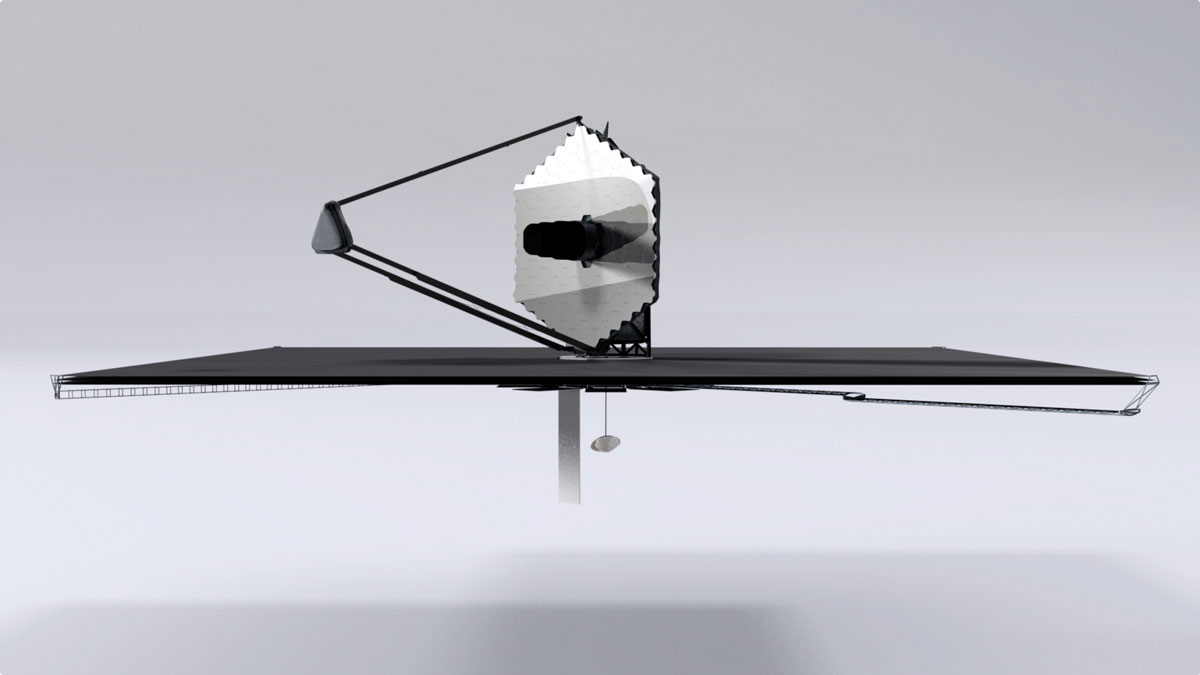

Dubbed the “real” successor to the ageing Hubble Space Telescope, the observatory would contain a mirror with a diameter of at least 6 m and cost around $11bn. The 20-member panel that wrote the report says that an independent review of the project’s feasibility should, however, be carried out before it is given the green light. Such a review would prevent the project from suffering the cost hikes and delays that have hit previous large space-based observatories.

Titled Pathways to Discovery in Astronomy and Astrophysics for the 2020s, the decadal survey was written by a committee convened by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Co-chaired by Fiona Harrison from the California Institute of Technology and Robert Kennicutt from the University of Arizona and Texas A&M University, it is the seventh decadal survey of its type. Astro2020 identifies the highest priority research activities in astronomy and astrophysics in the US over the coming decade.

The new report broadly identifies three “priority scientific areas” for investment over the next decade. One is to identify and characterize Earth-like planets outside the solar system, with the goal of imaging potentially habitable worlds. A second is to probe the nature of black holes and neutron stars. The third area is to improve our understanding of what happened in the earliest moments in the universe and of the origins and evolution of galaxies.

The main aim of the proposed observatory – which is the highest-ranked large space-based mission in the report – would be to search for biosignatures from some 25 habitable zone planets and to be a “transformative facility for general astrophysics”. Hubble, which covers wavelengths from ultraviolet to near-infrared, has been in operation in low-Earth orbit for more than 30 years but has recently suffered a series of failures in its electronics systems that could limit its lifetime.

Worth the wait

The two leading mission concepts in the infrared, optical and ultraviolet that are currently being worked on as a potential Hubble successor are the Large Ultraviolet Optical Infrared Surveyor (LUVOIR) observatory and the Habitable Exoplanet Imaging Mission (HabEx) telescope. LUVOIR has two variants, differing only in terms of the size of the primary mirror.

The panel says, however, that LUVOIR-A – which would feature a huge 15 m-diameter mirror made up of 36 segments – is too expensive an option. LUVOIR-B, in contrast, would contain a smaller, 8 m mirror and cost only £17bn. It features both a coronagraph and starshade that block out the light from a star so that nearby objects can be resolved. HabEx, meanwhile, is also designed to have a coronagraph and starshade, but with a 4 m diameter primary mirror would cost only $10.5bn. A smaller version of HabEx featuring a 3.2 m mirror would have an even lower price tag of $7.8bn.

The report says that the implementation of a single telescope based on the LUVOIR and HabEx concepts could begin by the end of the decade following a review to consider whether it is ready for implementation. Julianne Dalcanton from the University of Washington, who sits on Astro2020’s steering committee, told Physics World that the new telescope would be “the result of an intensive design and technology development process that would begin immediately”. She adds that it would “take advantage of the hard work of both the LUVOIR and HabEx concepts, pulling together the best of both to launch a large, capable telescope”.

Theoretical cosmologist Michael Turner from the University of Chicago, who has been involved in four decadal surveys and who was a reviewer on the latest incarnation, told Physics World that LUVOIR will do a “panoply of exciting science”. Turner adds that the launch date of early 2040 is daunting. “But as they say all the easy stuff has been done, and the ambitious plans we have these days take a long time to implement,” he adds. “But I believe [they are] worth waiting for.”

Those involved in the LUVOIR mission are equally delighted by the support from the decadal committee. Martin Barstow, a space scientist from the University of Leicester in the UK, who is a member of LUVOIR’s planning team, says the announcement is “a really exciting result” for the search for habitable worlds and life elsewhere in our galaxy, which he says is “one of the most important scientific quests”.

A mission like LUVOIR is the tool we need, and I will look forward to having that answer to the question ‘are we alone’ within my lifetime

Barstow adds that seeing LUVOIR so prominently in the decadal survey is a “testament to the huge effort of the team” over the past few years. “[Exoplanet research] is enormously challenging from an engineering perspective, yet we know how to carry out the search and are close to having the technology with which to do it,” adds Barstow. “A mission like LUVOIR is the tool we need, and I will look forward to having that answer to the question ‘are we alone’ within my lifetime.”

As well as LUVOIR and HabEx, two other large space-based missions were selected by NASA in 2016 to go forward into the Astro2020 process. They are the Lynx X-ray Observatory, which would replace the Chandra X-ray observatory that was launched in 1999. The other is Origins – an infrared space telescope. The committee recommends that NASA begin preliminary studies on both these missions, which would have a target launch cost of $3–5bn. However, it states that the next decadal survey should decide which one enters the implementation phase.

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, a theoretical cosmologist from the University of New Hampshire, is, however, disappointed by the decision to delay a potential go-ahead for Lynx as well as the general lack of emphasis on dark matter given its critical role in the universe, particularly in galaxy dynamics. “Perhaps the most disconcerting thing here is the delayed start for the proposed preliminary study for the X-ray mission – I don’t see a reason to wait,” says Prescod-Weinstein. “There’s been a lot of emphasis on optical, but it is also something we can do from the ground and where we already have new missions in the pipeline. We can’t do X-ray from the ground.”

Another major recommendation in the Astro2020 report is that NASA should establish a dedicated programme to develop the science, mission architecture and technologies of large missions that are identified as high priority. The so-called “Great Observatories Mission and Technology Maturation Programme” would advance the designs of several major overlapping space missions in the coming decades and provide early investment in the development of multiple mission concepts, changing the way major projects are planned and developed. A Hubble successor would be the first mission to enter this programme.

It is hoped that the programme will lower the risks and costs of projects before they become too complex and expensive. “Making up-front investments helps create mature missions with well-understood trade-offs between science and cost and allows NASA to move a sequence of exciting missions forward to launch at a faster cadence than possible if they were developed completely sequentially,” says Dalcanton.

On the ground

For the past two decades two competing designs have been battling it out to become the next US large ground-based facility. They are the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) and Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT). The GMT will be located at Las Campanas in Chile’s Atacama Desert while construction of the TMT began in 2014 but was halted a year later as native Hawaiians protested over how the astronomical community approached building the telescope on Mauna Kea, which they regard as sacred. Since then, TMT officials have chosen a site in La Palma should it not be possible to build in Hawaii.

Rather than pick one of these telescopes, the report says the National Science Foundation (NSF) should invest in both the GMT and TMT to “ensure significant access to these tools for the entire US astronomical community”. The report notes that the scientific potential of these observatories is “transformative, with the ability to address all three of the scientific priority areas and complement current and future space telescopes”. However, the report recommends that the NSF conduct an external review of the TMT and GMT by 2023 and if only one of these instruments can meet certain conditions, then the NSF should “proceed with investment in that project alone”.

“Investing in both telescopes is the ideal outcome for truly transformative science, provided both can be successful,” adds Dalcanton. “Rather than picking a winner and loser, the report offers a framework for evaluating whether the telescopes meet needed milestones before triggering federal investment.” Turner adds that the support by the panel to the GMT and TMT is “essential” to the future of US leadership in astronomy and astrophysics. “Not only will NSF involvement give access to all US astronomers, but it comes at a time when both projects are in need of financial help,” adds Turner.

Astro2020 was expected to be released last year but was postponed due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and many subsequent meetings had to be moved online. Astro2020 includes the input of more than 150 scientists and drew from the astronomical community through hundreds of white papers, town hall meetings and the advice of 13 sub-panels. These included six science panels and six programme panels, as well as the first panel focused on the state of the profession and societal impacts (see box below).

Dalcanton says that the report sets out a clear and “ambitious” vision for the coming decade – a view that is shared by Turner. “The most exciting breakthroughs in all of science are occurring in astrophysics and the life and biological sciences,” adds Turner. “Both are transforming our understanding of our place in it all – and both are powered by instrumentation that is enabling us to be able to explore two these worlds that have been beyond our reach.”